Women’s emancipation: a slow process

Labour participation rate of women steady during crisis, then rising

During the recent economic crisis, the labour market participation of women did not rise. The proportion of women in paid work has stayed around 70 percent already since 2008, though more women have since registered as jobseekers on the labour market. On the other hand, relatively more men lost their jobs during the crisis as they tend to work in sectors which are more affected by economic fluctuations. Consequently, the gap between female and male labour market participation has still narrowed. Since the economy entered a recovery path in 2014, more women (and men) who were registered as unemployed have managed to find work more easily and the female labour market participation has gone up accordingly.

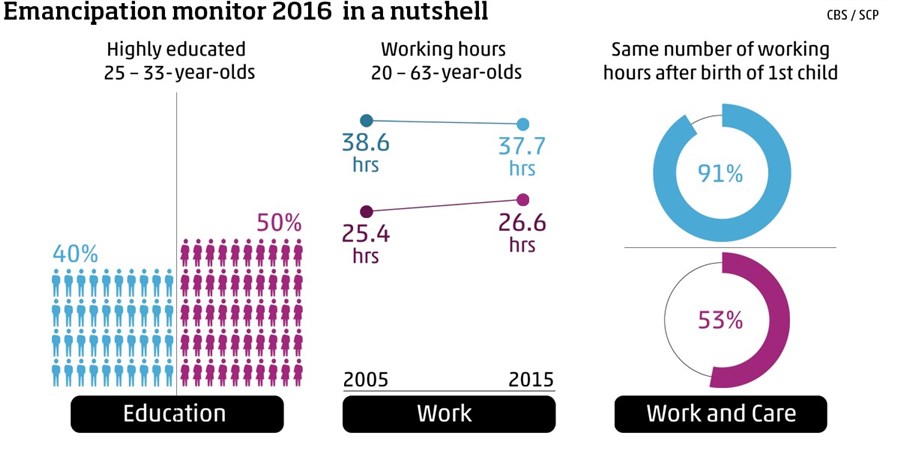

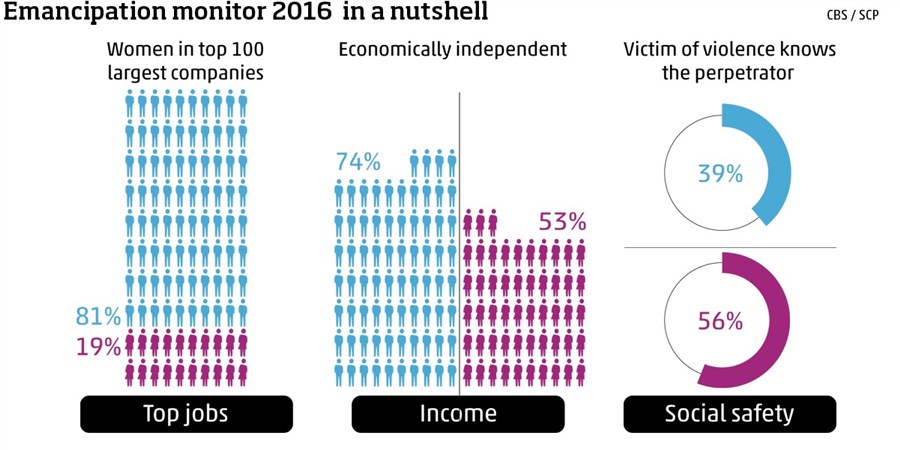

Furthermore, the share of economically independent women is increasing slowly. Last year, 54 percent of women and 74 percent of men aged 20 to 64 earned more in paid work than a single person receiving social assistance benefit (a net amount of 920 euros). For women as well as for men, this is one percentage point up from 2013.

Mothers continue to work more hours

In 2015, the average working week of women was 26.6 hours, over one hour longer than in 2005 and 20 minutes longer than in 2013. Men worked nearly one hour less compared to 2005 with 37.7 hours. Working hours of women with a partner and young children increased relatively sharply between 2005 and 2015, and with it their economic independence. Having children increasingly rarely becomes a reason to stop working or work fewer hours. Women in their thirties work half a day per week more on average than women of the same age in previous generations. Hence, there appears to be some movement in women’s working hours.Half of young fathers have weekly parenting day

Equal sharing between parents of work, household duties and care tasks is still a long way from reality. Women predominantly work part-time jobs, even when not raising any small children. Men tend to cling to their weekly full-time schedule, even when they do have small children. That said, half of the men who recently became first-time fathers opt for a weekly half or full parenting day (‘papadag’). Most of them take up parental leave or start working flexible hours. As for young mothers, nearly all maintain at least one parenting day (‘mamadag’) a week. They are twice as likely to take up parental leave. This difference between mothers and fathers is not being reduced. Women are also more likely to care for sick parents (or in-laws) and other sick family members.

Divorce means 25 percent less purchasing power for women

In 2014, men were the main breadwinners in seven out of ten couples. This proportion was slightly higher ten years earlier. Most Dutch people believe it is important that women should have their own income. They also believe that in a good relationship, an income difference between partners is not an issue. It does become an issue, however, when a couple breaks up: over one in three relationships ends in divorce, and in this case women lose a quarter of their purchasing power at large, while men are rarely disadvantaged. Loss in purchasing power also affects women who receive maintenance in the form of partner alimony. As the number of economically independent women grows, partner alimony becomes increasingly rare.Women earn lower incomes than men

Women are less likely to earn their own income than men, and the income they receive is lower on average, for various reasons. Firstly, women work less often than men or more often work part-time. Their average hourly pay rate is however also lower. A major reason for the wage gap are differences in work experience, education level and management level. Wage differences have decreased since 2008 in the civil service and in the private sector.More women at the top in private sector and civil service, not in non-profit sector

The share of female top civil servants having gone up from 28 to 30 percent means the Dutch government has achieved its target. There has also been a slight increase in the share of female professors and female managers at the highest level in the commercial sector. The presence of women in the board of directors or supervisory board of the 100 largest companies in the Netherlands has risen to almost 20 percent, a substantial rise compared to the situation in the past. In the non-profit sector, one in every three to four senior positions is held by a woman. Yet it is in this sector, with relatively many female employees, that the share at the very top has not increased (care and welfare) or has even decreased (socioeconomic sector and civil-society organisations).Health more often reason for not working than care tasks

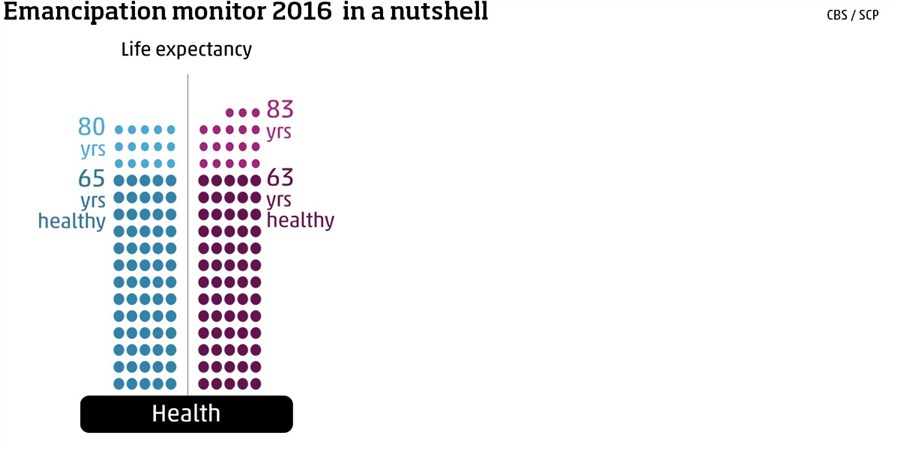

Not taking up employment is increasingly rarely because of running a household or care tasks for women. This reason applied to only 4 percent of women in 2015. Poor health conditions are twice as often the reason for women unable or unwilling to accept work. The number of women not working due to health reasons has furthermore increased, and is now over one and a half times higher than among men.

These are some of the conclusions from the Emancipation Monitor 2016. The Monitor is published under joint editorship of the Netherlands Institute for Social Research (SCP) and Statistics Netherlands (CBS) at the request of the Minister of Education, Culture and Science, who is responsible for emancipation policy.